air and fire

The invention of truths

Oami on Mount Haguro in Japan, is a small village in which there is a temple in which is kept and venerated the mummified body of a monk who in 1783, at the age of 96 years, was buried alive.

Since the age of 20 years, he decided to become an ‘eternal monk’ in order to protect people for the eternity, so he began a practice, strict and terrible. His diet of nuts and special infusions, allowed him to cool off in the summer and burn fat slowly during the winter, to avoid putrefying once he became a mummy. After the burial he breathed through a bamboo straw, reciting mantras and meditating he resisted about three and a half years, during which he gave signals of his being alive with a bell that he rang. This comforted and consoled his disciples. To this day, his mummified body is still venerated, cared for and dressed every six years as if he were still alive. Shugendo, the religion practiced by these monks is a mixture of syncretic Buddhism and Shintoism that has as its main objects of veneration, the mountains and the air.

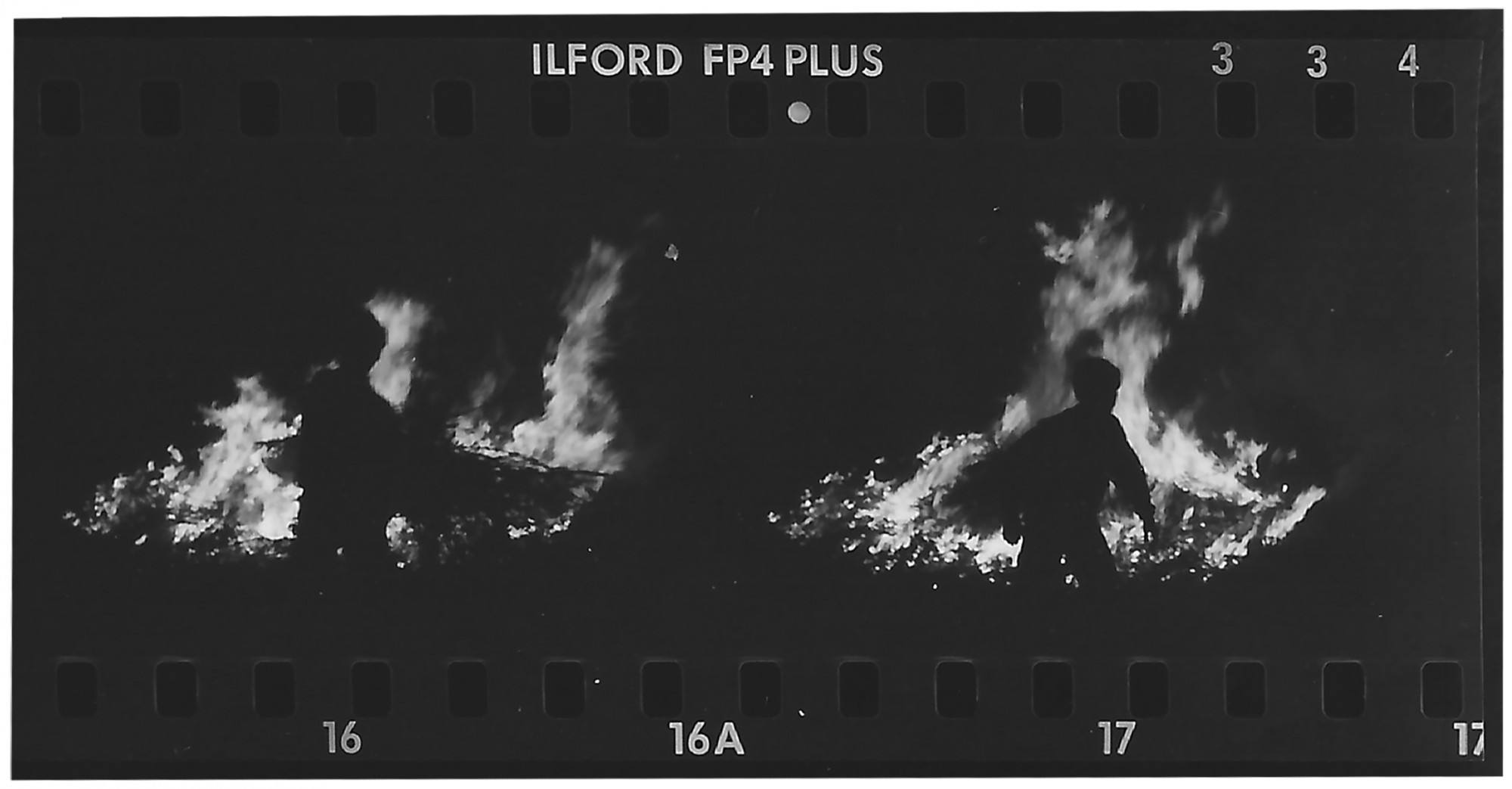

In the province of Matera, towards the end of the fifteenth century, there are traces of a ‘masciara’, a witch who inhaled the air of women, sick of mind or nerves, and healed them. According to the legend she wandered in an area between the towns of Miglionico, Pomarico and Montescaglioso, a triangle called ’tre cunfin’ (three borders). During the summer nights with a waning moon, it seems that she approached young women in their beds of suffering and inhaled the air around them for a few minutes. The sick women would fall into a deep sleep but upon awakening, they would find themselves healed and perfectly healthy. In the following nights until the new moon, the male villagers of the ‘cured’, hid in the house because the witch continued to wander around looking for men to whom give the disease. Every year on the first evening of the waning moon in July, a fire is lit in the center of this triple border and the healing witches are worshipped. Witches prefer the woods and nature where everything originates including the mythology that accompanies them, their strength is linked to independence and knowledge of the most archaic and profound mysteries of the primordial elements: air, water, fire and earth.

Already at times of the Etruscans, the aruspices existed, priests, often women who interpreted the entrails of animals. The ’fulguratores’ became intermediaries with the divinities thanks to their ability to decipher the phenomena related to the air, they understood the will of the gods by observing the trajectory of lightning while the Augur interpreted the flight of birds.

Fantasizing the existing: rituals and copies

Gaston Bachelard in Le dormeur éveillé writes: ”Our belonging to the world of images is stronger, more constitutive of our being, than belonging to the world of ideas”. What seems to be an unconscious trance is, on the contrary, consciousness of the fantastic abandonment, of fantasies, in fact, according to Bachelard: ”one can only study what one has first dreamed. Science is formed more on a reverie than on an experience and many experiences are necessary to clear the mists of the dream.” Following the rêverie as a tool that opens up the single natural vision and brings it back as an archetype in the history of human collectivity, we should not take into account the Jungian doctrine of the symbol nor the Lacanian regimentation of the sighted, we should rather look at the field of social learning as a tool to link fantastic vision and social repetition. Think of the death-rebirth call of many peasant or pagan rituals that symbolize this passage and that follow the continuous alternation between active and passive.

Peasant rites linked to nature, perform an important institution for the definition, management and organization of time, often through reveries, tales, stories or festivals. The repetition of the ritual, not always religious, spreads the usefulness of the practice thanks to the processes of imitation, but the relationship between man and nature is often distorted by contingencies, by the “needs” of the present, as Murray Bookchin reminds us:

”An ecosystem is never a random community of plants and animals that occurs merely by chance. It has potentiality, direction, meaning, and self-realization in its own right. To view an ecosystem as given (a bad habit, which scientism inculcates in its theoretically neutral observer) is as ahistorical and superficial as to view a human community as given. Both have a history that gives intelligibility and order to their internal relationships and directions to their development. […] human history can never disengage itself or disembed itself from nature […] Humanity’s involvement with nature not only runs deep but takes on forms more increasingly subtle than even the most sophisticated theorists could have anticipated. Our knowledge of this involvement is still, as it were, in its “prehistory.”

Bookchin demonstrates how the distorted idea of the interaction between the living and non-living kingdoms starts with the concept of hierarchy:

”no liberation will ever be complete, no attempt to create harmony between human beings and between humanity and nature will ever be successful, until all hierarchies and not only classes, all forms of domination and not only economic exploitation, have been eradicated […] evolution must be considered as a participatory phenomenon, not as Darwinistic ‘natural selection’ of a single species on the basis of its ‘suitability’ for survival. Animals and people evolve in communities, not as ‘solos’. […] That of the soloist is the typical image of the isolated individual evoked by the tradition of Anglo-American empiricism, particularly Hobbes and Locke.”

Therefore, unity in diversity means that nature is not simply a “realm of necessity” as Marx would say, but a realm of nascent and potential freedom that could find its full expression in an ecological society created by fully realized human beings. So can we finally imagine a “sustainability” that starts from the ability to generate dialoguing machines (tools and modes) with the same speed and ease with which the territorial exploitation (economic, communicative and social) of the producing machine manages to penetrate the territories to extract value from them?

The places of abundance

Giovanni Attili in the book ”Civita” describes in detail the parable of the Lazio village of Civita Bagno Reggio, a small village between Lazio and Umbria, that in 2018 was the destination of nearly a million visitors compared to a dozen residents and about forty owners of second homes:

”The almost philological renovation of almost all of the heritage has allowed us to celebrate a form capable of resisting the oblivion of vanished worlds. It is an urban form that, even though it hosts radically discontinuous uses compared to the past, allows itself to be seen by visitors as an iconic representation of a coherent and communicable memorial identity. And it is precisely this form, detached from the vital worlds that had produced it, that transforms itself into a spectacular backdrop, a background of surprising beauty, the suggestive and picturesque scenario within which Civita concedes itself as an aesthetic object to be enjoyed as a work of art. Once the vital working relationship with the territory has been definitively severed, Civita therefore makes itself available for new forms of fruition, in which the processes of aestheticization which initially interested a restricted and elitist group of professionals and intellectuals, begin to concern large portions of the population.”

With Bookchin’s eye, one wonders where is the deception hidden in giving visibility, in transforming into a scene, into a spectacle, into merchandise (in this order) not only the places, reconditioned on the visual actuality, but also the uses, the real practices, alive and necessary to the sustainability of those places, relegating them to the so-called cultural consumption to the all-pervasive tourist monoculture?

Many houses are simple reconstructions in style […] like the blatantly false interventions sometimes applied as paintings on the facades of some buildings […] the surviving plots of past life forms are frozen on the pages of a tourist guide. They no longer bear with them the traces of a continuously operating time, they do not materialize a becoming that lasts, a change that constitutes the very substance of it. The continuous metamorphosis of these survivals no longer carries the memory of the investments of meaning that have thickened over time. Everything becomes a monument, a mere petrified objectivity closed in on itself[…] The danger is a fossilization of the landscape, a trivialization of the living: a process that risks transforming Civita into a lifeless postcard, into a museum.”

The question that interests me as an artist, and which is becoming increasingly evident, concerns the search for and use of new aesthetic ‘processes’ that avoid the constant subsumption of ‘forms of life’ and consequently the rupture of relations between man and the environment. The technical and methodological colonization risks to degrade the work of man in nature: from relationships to objects, from uses to management, from work to defense, from story to history. In the last decades we have witnessed the widespread diffusion of ’new artistic techniques’ especially in peripheral territories; moving research to ’other places’ has also led to the diffusion and decentralization of the concept of ‘artistic practice’. Gradually, with different definitions: relational art, urban art, public art, participatory art, community art, performative art, peripheral ‘contexts’ have been furnished thanks to the mediation of local institutions and the use of suitable formats such as residencies, workshops or, more often, exhibitions. Perhaps we need to learn to look inside a process not to see and recognize creative mechanisms but to discover aesthetic frames and therefore works, if we still want to use this term, capable of nourishing the constellation of expectations, hopes and visions generated by a work of this type that is difficult to complete definitively. It is not the formalization or the conclusion that is the purpose of these ‘programs’ but the very existence, prolonged and continuous, of doing.

I never had any illusions that I could change the world. I’m interested in how things are done, I’m interested in the means, not the end. The means used is already the end to realize. (Paolo Finzi)

The invention of truths

The development and massification of these forms of expression, which now involve all cultural, social and political aspects of the territories, suggest greater attention and respect in the confrontation with the souls of a place, because involvement, participation and relationships must be kept alive and nourished over time and not extrapolated for exotic representative outings. Returning to the symbolism of ritual in small communities, I must confess that one of the two initial stories is false and both have been exaggerated. I deeply believe in the narrative sense that defines a small community and that is continually “formed” also through invented, falsified and exaggerated stories and tales and thanks to the characters that pass through it and that are often marginal, degraded or excluded figures.

I can’t stand a damn liar and have no respect for one. But an artful exaggerator always gets my full attention and my undying respect. (Nat Love. Paradise Sky, Joe R. Lansdale)

As far-fetched as they may be, these stories run within the perimeter that defines customs and traditions, they serve to enrich a communitarian existence and in their own way, contribute to define the customs and traditions of a place. By overlapping and coinciding with reality, art runs the risk of tracing sociological and anthropological research, often outdated, and defining relationships only from a representative and consolatory point of view. On the contrary, the continuity in time produces articulated knowledge that brings us closer to the community, right into the ‘sacred’ belly of the symbolic rites. It is the role of the author and of the research that changes: not a deus ex machina but a member of a community, not a project to be admired but a contribution to the growth of a place. Time allows us to understand customs and habits, it does us the honor of inviting us to share food and wine.

Sometimes what we can produce are two simple actions: inspire and exhale.