Giorgio Lolli

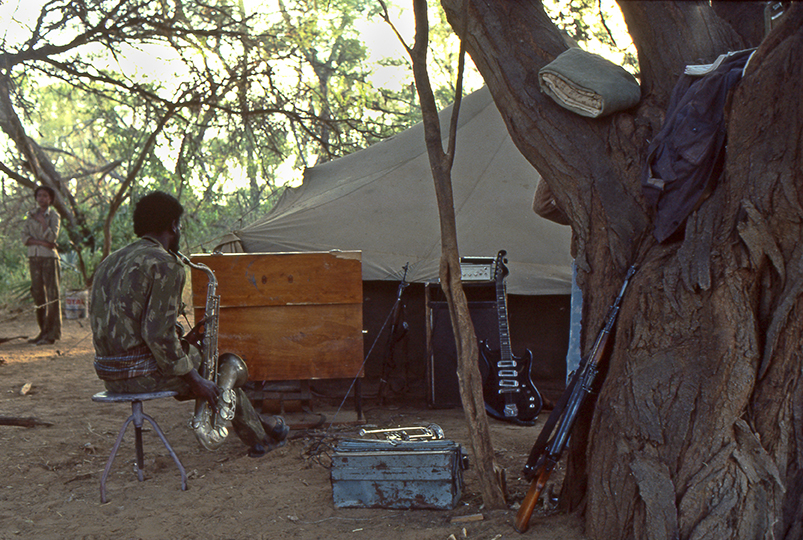

From Bologna, by birth, seventy-year-old former laborer and trade unionist, freelance cameraman and documentary film director, Giorgio Lolli is to be considered in effect as the father to African private radio stations. In forty years of activity, as he was nicknamed in Africa, ‘Monsieur Lollì’ has founded more than 500 radio stations, from Togo to Mali, from Senegal to Burkina Faso through Benin and Eritrea. A journey started in 1978 when, with two friends and his video camera on his shoulder, he decides to film a documentary about Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF). While on site, a radio link allowed the guerrilla fighters to keep contact with a group of Palestinians in Jordan. A menial technical problem was preventing to broadcast properly: Giorgio solved it in a few minutes. At that point, the fighters asked him if he was capable of building a radio that would make contact with the remaining portion of the insurrectionist movement: this is how his African adventure started.

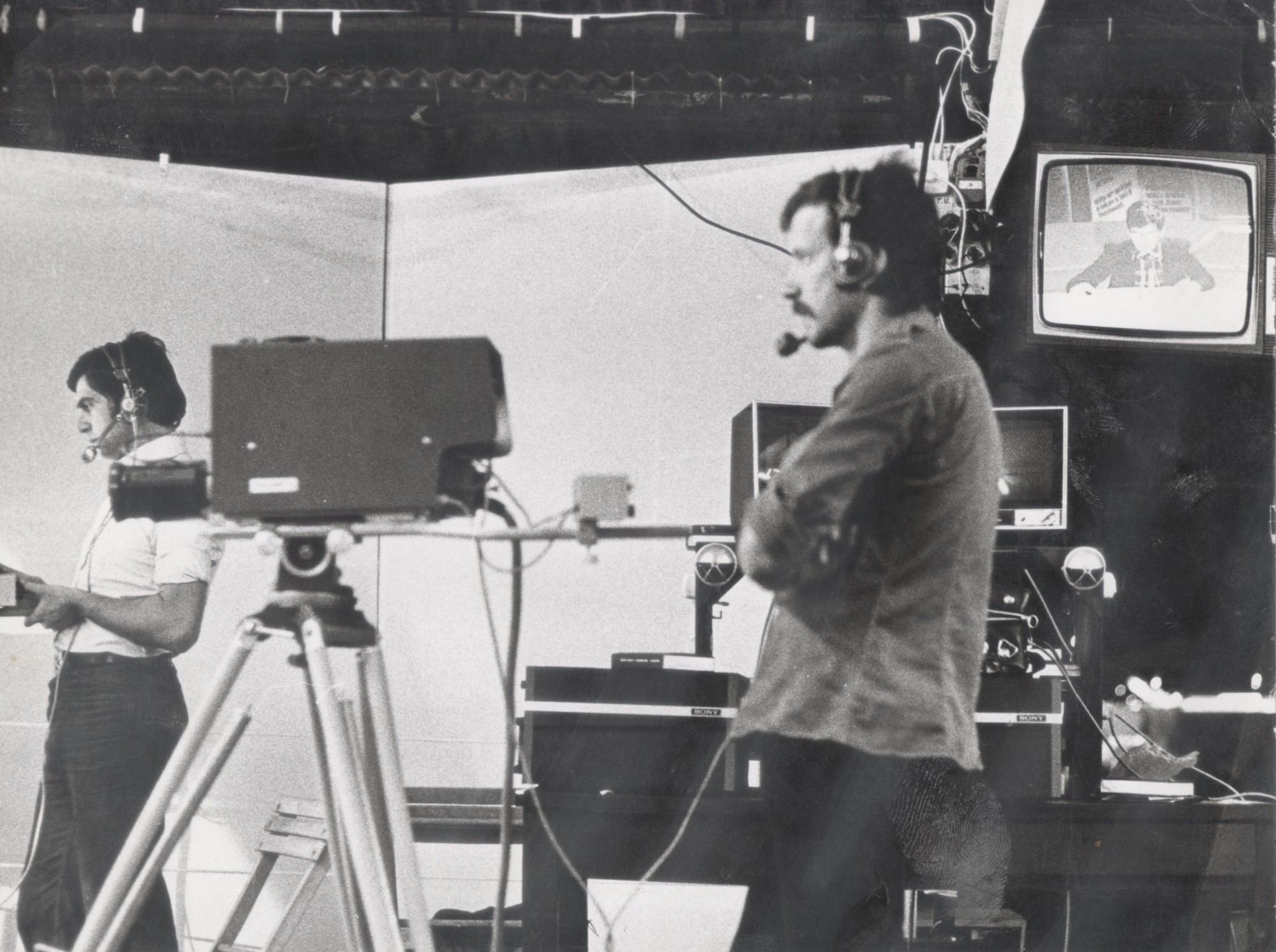

Actually his story starts way earlier in time in Bologna. Laborer and trade unionist at Carpigiani company, Communist Party activist, with passion for radio and audiovisual techniques, it is Lolli who dismantled the studio of the historical ‘Punto Radio’, the station located in Zocca (Modena), where Vasco Rossi started his career as DJ. He moved this station to Bologna, when the Communist Party decide to buy it and turn it into a TV channel, too. This way, Giorgio becomes one of the cameramen of the rising ‘Punto Radio TV’: his is the shooting of the Bologna massacre at the Central railway station in 1980; his is the shooting of the National Convention against Repression in 1977, as well as those during many Communist Party events at the time, besides some of the shootings of the rising gay e lesbian movement in Bologna. He also plays a purely technical role in the birth of the first ‘telestreet’ in Via del Pratello, called Prate TV.

However, his true passion remains the radio. And Africa.

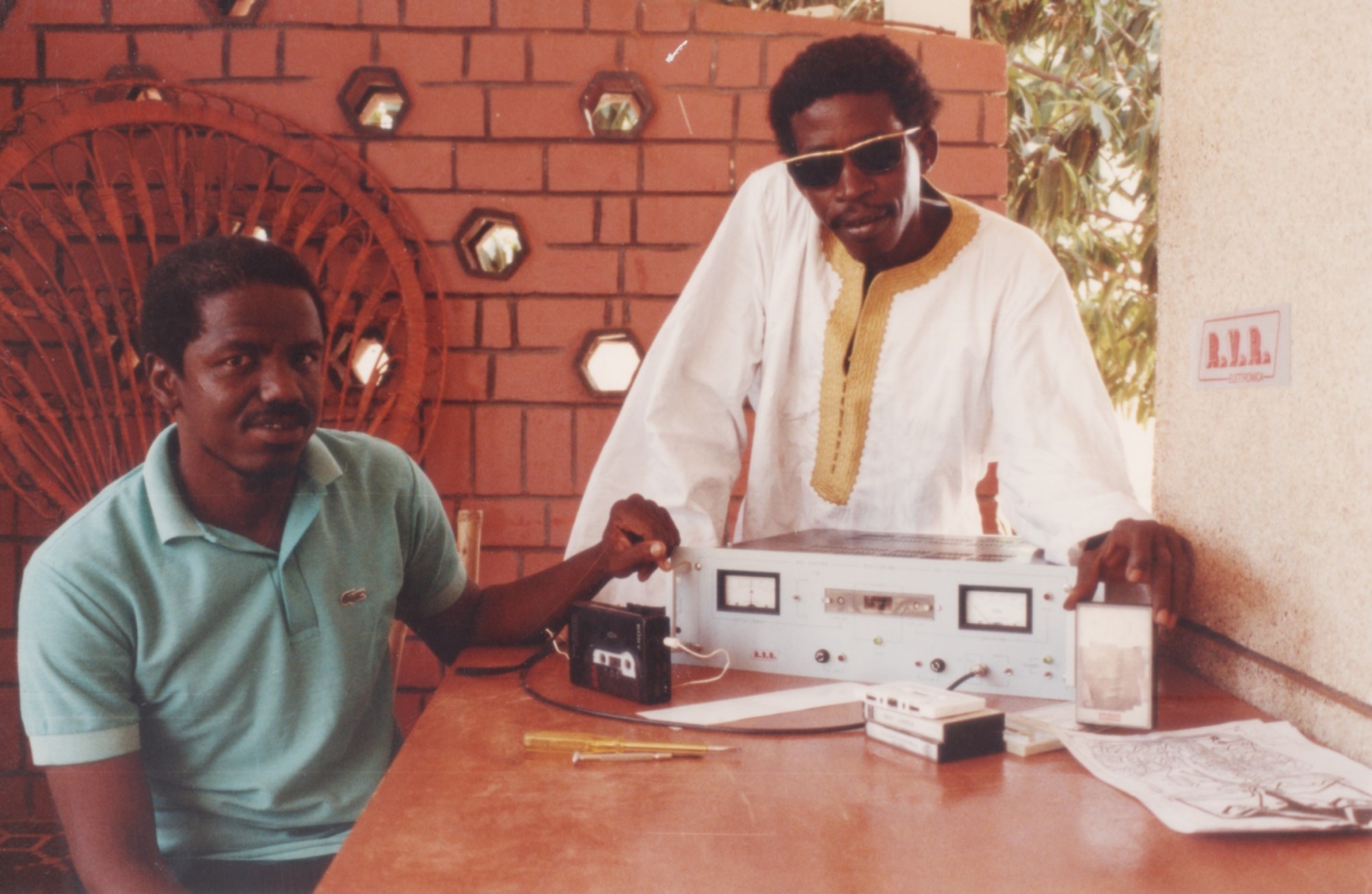

In 1991 he lands in Bamako in Mali: in his suitcase he has an antenna disguised as an electric scalpel unit. While at customs, he declares it is sanitary material. Outside of the airport there is a lot of turmoil: the dictatorship of General Moussa Traorè is close to an end. During the night, in secret, Giorgio assembles his basic equipment, mounting it on a pole, covered with vines and starting from the following day he starts broadcasting. From that point onward, thanks to that radio as well, the dictatorship falls. Days of extreme confusion follow: his video camera on, Giorgio shoots the total of it. In the liberated Mali, Monsieur Lollì founds the first free radio station. Its name will be Radio Bamakan, ‘the talking crocodile’. At present, it is still one of the mostly popular radio stations of the Malian capital.

After this experience, and thanks to a law on FM frequency liberalization that was promulgated at the same time in different African countries, Giorgio realizes the potential of this means and he founds in Togo, a company called ‘Solaire’, that builds radio stations here and there all over Western Africa. They are big and small radio stations, state and village ones, religious and non-governmental ones, farmer association ones, too. They often call them ‘rural radios’: they are community radios, often managed by the whole community. They talk to people about their problems in their own language.

Radio is the most democratic means of communication, as it is accessible to everybody. The poor ones live without electricity, no TV, no phone nor computer. The illiterate ones cannot read the newspaper. Radio, instead, can be listened by everybody. ‘Even in the most isolated areas, Africans always have a radio to their neck. Radios worth a few pennies, from which they can never separate from.’

Lolli’s philosophy is to produce ‘technically reliable, easily accessible and especially inexpensive’ devices. The first years of activity, Solaire was forced to import and assemble them in Africa, ‘now, instead, the vast majority of the devices needed for radios to function are produced here, in our workshop in Lomè, in Togo.”

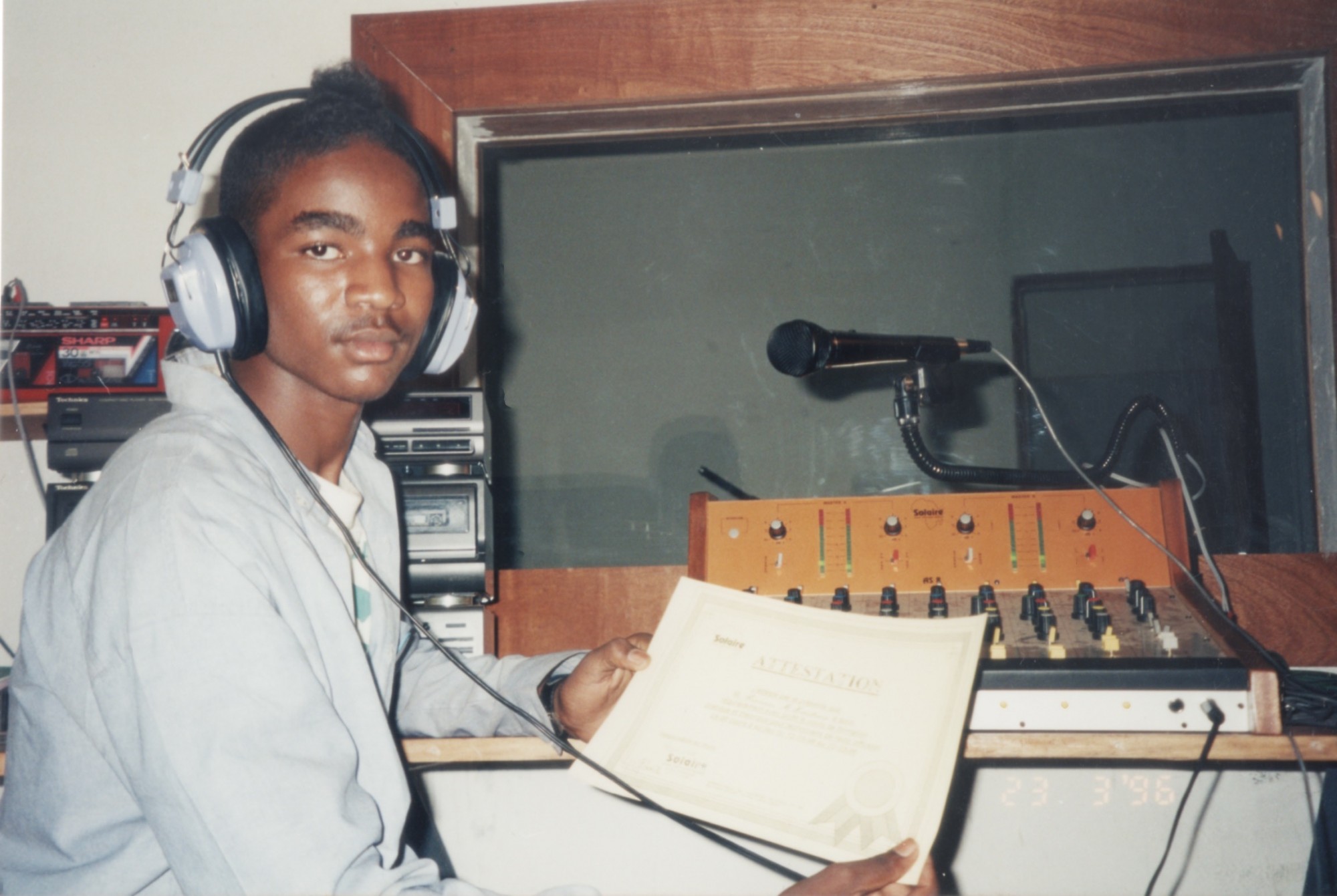

In a continent where the majority of westerners try to exploit without giving anything back, Giorgio opened two training schools (in Togo e in Benin), where he teaches ‘his guys’ the basics of radio broadcasting: build and mount an antenna tower, broadcast and organize a radio schedule, fix minor and major issues. In twenty years, his schools trained hundreds of technical and specialized workers, able to, when their turn come, to spread all the technical skills all over the continent.

Basically, those that buy a radio at Solaire, besides the device and its installation, they also obtain to be able to send a couple of technicians to school, where they are hosted for free to attend courses. As a consequence, the radios, once installed, are independent from the company that built them and in case a device would break in the middle of the desert, the manager themselves are able to fix it.

In the same building that hosts the school, Lolli also gave birth to X-Solaire, his own radio. It is himself, who, gives the editorial line, telling the listeners about significant celebrations, such as March 8 or May 1 (Labor day), teaching to recycle and pollute less. He explains what is needed to migrate to Europe, without ending up in the human trafficker’s hands. Moreover, he makes his collection of historical and political books to those that work with him. He would end up gifting those books and contributing to the education of his employees.

During these forty years in Africa unpleasant episodes happen: X-Solaire itself was closed many times with ridiculous excuses, Giorgio himself was arrested, though he always have been released. Not to mention the robberies or the jobs he would never be paid for the majority of the time: the African adventure did not make him richer with money. However, the chance to give voice to isolated communities in the desert, the chance for information to go around and confront ideas represent a revolution that has a priceless value, for an old-style idealist like Giorgio. After all, he has never been a real business man, rather a red missionary, as his friends love to define him.